Exploring the Budapest’s Underground Caves

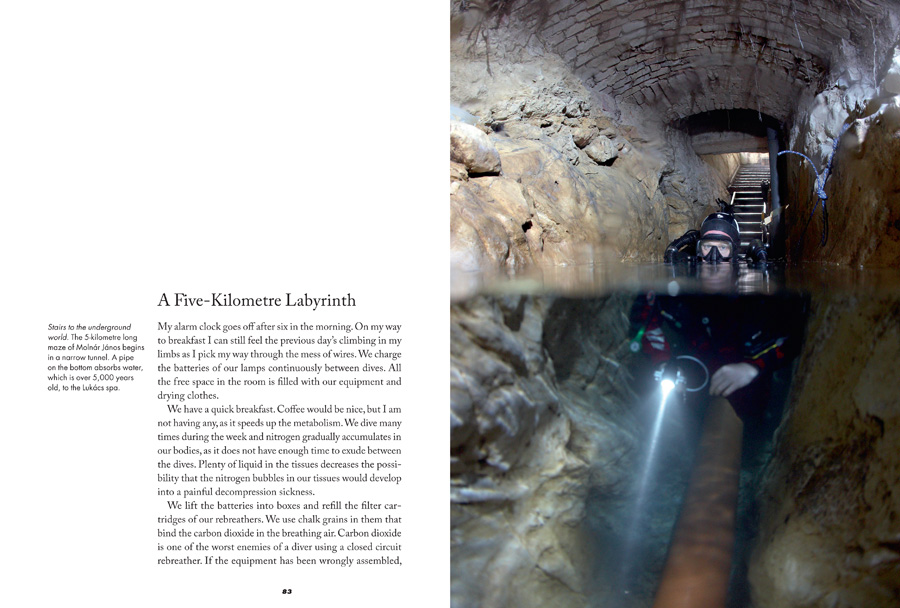

Budapest is known for its spas. Their water originates from the volcanic earth. One of the most well-known springs is Malom Lake. It is a doorway to the cave system called Molnár János. Only a part of it has been explored so far. Nobody knows how far or how deep below the city the tunnels reach.

Divers of the Dark is a unique journey into an underground world that only a handful of people have visited. The magnificent photos take the reader on an adventure into the depths of an inactive volcano. The caves are a prehistoric nature park that has been formed over millions of years. The photographers took their cameras to places where nobody had ever been before.

Divers of the Dark tells stories of journeys of many kilometres under the ground, of near miss situations and incredible human achievement. It will give the reader a whole new view of the life and surroundings of Budapest.

The book is an exciting, fascinating introduction to cave diving. Its photographs give a rare insight into an underwater world.

The book is suitable for everybody who is interested in adventure and diving. The book also takes the reader to the József-hegy dry cave in Budapest and the water filled Ojamo lime mine in Finland.

Ojamo mine

Ojamo lime mine is situated in Lohja, some 60 kilometers west from Helsinki. The mine is the most popular cave diving site in Finland as there are no diveable natural caves. The conditions for diving are excellent all year round. The ground water is crystal clear and there is current.

A several kilometre-long network of tunnels begins at the bottom of the quarry. The mine tunnels pierce the granite and follow the lime vein that snakes through the basement rock. Inside the rock there are immense mine halls, connected one after the other by the tunnels like a pearl necklace.

New tunnels are constantly explored. The longest dives are a couple of kilometers from the entrance. The longest tunnels are at he 88 meter level, which has been the main mining level of the mine.

Ojamo’s many kilometres of tunnels offer plenty of things to photograph. The mining industry in Ojamo was at its busiest during the first half of the last century. After the war mining was still practised, but gradually the mining of lime from a deep mine became unprofitable. The mine was closed in the mid-60s and the pumping of water from the mine was stopped. The mine filled with water within a few years. Diving was first practised in Ojamo in the 1970s. The water in the mine reaches at least 200 metres deep.

The mine is full of things people have left there. Abandoned tools and dynamite boxes rest on the cave floor. A wheelbarrow has been left at the foot of the stairs ready for the next shift. The electric lamps are hanging off the ceiling as if waiting for the lights to be turned on again.

Diving is more pleasant in Ojamo than in the often dim waters of the Gulf of Finland. The water of the mine has been slowly filtered through the soil and is therefore crystal clear. The temperature of the water inside the rock is approximately four degrees all year round.

During the Second World War, Russian prisoners of war mined the rock in shifts and lived in tents erected in the strip-mining pit. In the winter they only had enough mantles for the men working their shift.

The place names written on the map by divers describe the visitors and visits to the mine. For example, under Lake Lohjanjärvi there is an enormous concrete construction called the Gates of Hell that supports the ceiling of the mine. Due to a calculation fault the miners nearly drilled through the bottom of Lake Lohjanjärvi. A support was built when they realised that only a few metres of rock separated them from the mass of water.

Crystals of József-Hegy

“Every now and then I pull myself through holes, having no idea of the several-metre falls that wait beyond them. I wish that I had refreshed what little rock climbing skills I have before the journey.

We have almost reached the bottom. I lie down on my stomach and peer through a small hole. My mind argues strongly as I wonder how to get through the narrow gap. If I did not know that Szabolcs, who is much bigger than me, has just gone through it, my descent would end here. I take a deep breath and, kicking strongly, plunge head first into the gap. I extend my hands and pull myself forward centimetre by centimetre. The distance of a few metres feels like an eternity. My fingers slip on the surface of the clay-covered stones. The others’ encouraging calls sound distant.

I get through and struggle to my feet. I take a few steps forward and peek down the next steep drop. I turn around and look at the gap that I have just come through. At first, I cannot see it at all. I realise how easy it is to get lost in these caves. The route that looks most obvious is not necessarily the way out, but often takes you deeper into the many kilometres of caves.

The view that opens after the last gap is breathtaking. The immense underground hall before us developed a million years ago in the depths of the mountain. The surface of the water gradually descended in the area, and the caves dried out completely approximately 210,000 years ago. I can imagine how Szabolcs and Péter felt when they first saw this, 25 years ago. This find is every cave adventurer’s dream.

The lights of our helmets form a chain that wanders quietly through the halls. The atmosphere is solemn and somehow unreal. Szabolcs takes us from one hall to another, showing us most extraordinary formations. Every now and then we crawl in clay tunnels.

The surface of the water has slowly descended in the cave. Where the pond used to be, calcium carbonate has dried into glittering plates that are like ice. Crystals are attached to stalactites and projections in the caves. They look like ice decorations. The shades of colour vary from bright white to the dark brown of the stalactite.”

Molnár János cave - A Cave Diver’s Dream

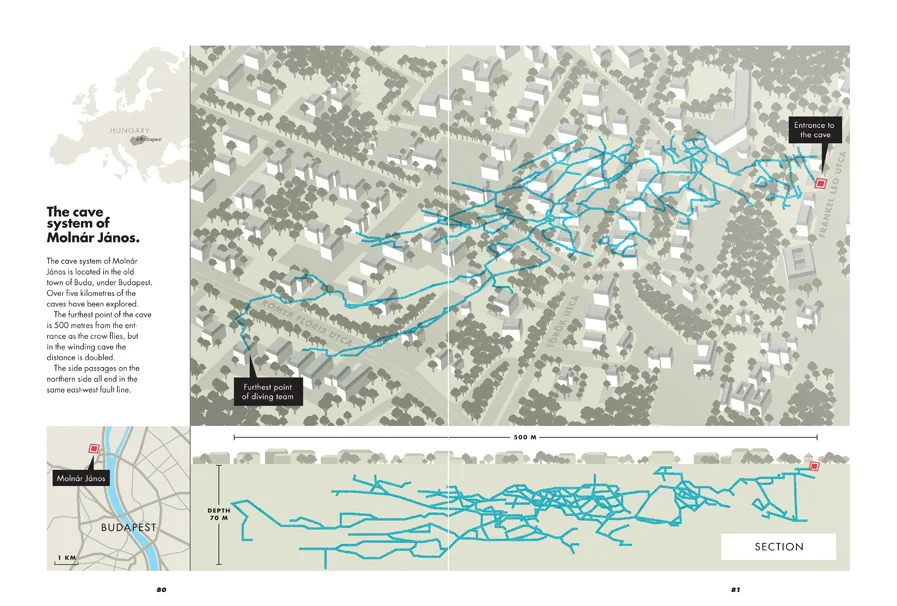

The Danube River divides Budapest into two. Buda is situated on the west bank of the river and Pest on the east bank. The caves of Molnár János are located on the side of the old town of Buda, near the Isle of Margaret. There are popular parks and spas on the island.

The spring of Molnár János flows to Lake Malom. The name 'lake' is a slightly grand definition for a pond that becomes eutrophic in the summer. After a few hundred metres it flows to the Danube. The lake was already known during the Roman Rule – divers have found Roman constructions at the bottom of the pond.

The Hungarians settled in the area in the 10th century. The waters of Molnár János were dammed in the 13th century to create the pond, which in turn served to power mills. The first written records referring to the spring are from 1276, when the Pope donated the pond and its mills to the Isle of Margaret’s nuns.

The earliest information about the caves is from 1858. János Molnár, a pharmacist, investigated the dry areas of the cave and analysed the water of the spring. He examined the healing effects of the water. The actual cave research began in the 1930s and in the 1950s divers dived there for the first time.

Over five kilometres of the caves have been explored. The biggest charted hall is over 80 metres long and 16-26 metres wide. In this hall alone there is over 23,000 cubic metres of warm water. If an ordinary kitchen water tap was installed at the bottom of it, it would take four and a half years to empty it. There are hundreds of these halls in the caves.

Drilling in the surroundings of Molnár János has revealed that there is a network of many caves crisscrossing between 150 and 250 metres deep underground. Most cave divers never reach such depths. The tunnels of Molnár János continue towards the depths, but so far divers have only reached the depth of 75 metres. The exploration of the cave system continues.

In the Depths of the Limestone

Budapest’s limestone earth developed during the warm and humid Eocene period approximately 30-50 million years ago. The first animals like present-day mammals also developed at the same time.

Hungary is bordered by the Carpathian Mountains in the east and the Alps in the north. The rising Alps lifted the Buda mountains with them. The ground plate of the Pannonian plain sank eastwards. The ground cracked along the collision line of the mountains and the plain. Ground displacements can also be seen in many places in Molnár János, where the cave ends as if it had been cut with a knife.

The caves developed when the top layer of earth cracked and stair-like depressions developed in it. Later, water started flowing in the cracks. The muddy soil layers were a barrier that prevented the surface water from flowing deeper. The hot currents that rose up from the depths through the cracks brought up mineral-rich acidic water. Millions of years ago there was also a volcano on the site.

The cracks in the lithosphere were formed afterwards by both the water running from the surface and by volcanic gases. The gases rising up from the lower earth layers contain hydrogen sulphide, which becomes sulphuric acid when mixed with water.

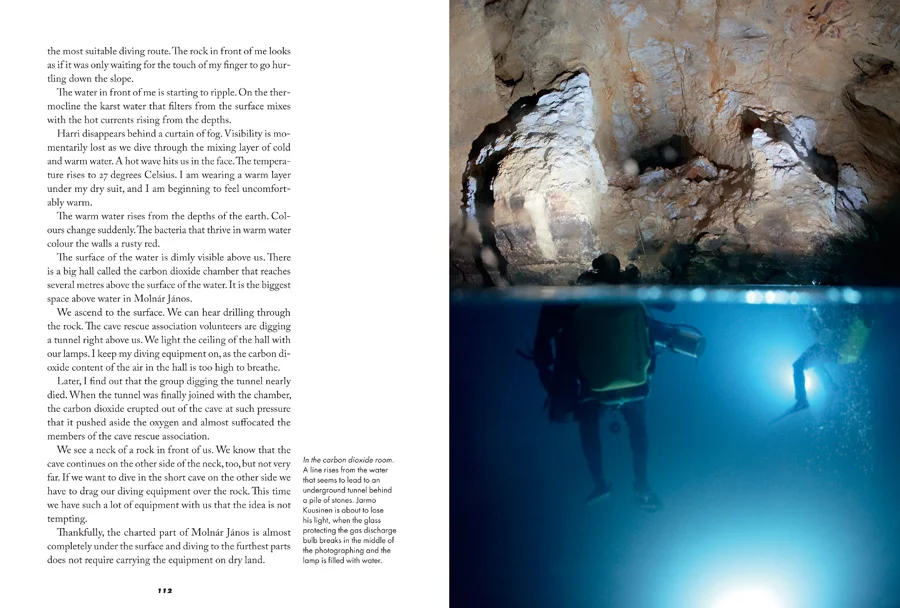

Divers call the water in Molnár János hostile due to the sulphuric acid it contains. There is so much sulphuric acid in the water that it erodes material, especially rubber and metal. The metal surfaces of the diving equipment darken within a few days in the water. The diving suits and breathing regulators must be replaced frequently.

In Molnár János new caves are still being formed, but the speed is quite slow in terms of human lifespan.

The humidity exuding from the earth’s surface gets mixed with the rising ground water that has rained down thousands of years ago. According to radiocarbon dating, the ground water in Molnár János is over 5,000 years old. The fossils in Molnár János originate from the time when the area was sea bed. The ground layer where the cave is located mainly consists of red algae, echinoids, coral fragments, bivalves, decapods and bryozoans. The mystery of Molnár János is what hides underneath the many metres of silt sand.

The most magnificent details are the crystals on the walls of the cave that are formed from orthoclase and barium sulphate. Orthoclase develops when silicate and calcium carbonate are crystallised in water. The particles of soft limestone have crumbled down to the bottom of the cave and become silt. Gradually harder fossils emerge from deep inside the rock. They stick out of the wall for a while until the limestone surrounding them erodes and the fossils sink to the bottom.

In Molnár János the water flows very slowly. In the deeper part of the caves the silt sand that has run down from the upper levels covers most of the bottom, hiding its contours. The currents are so weak that they cannot carry the silt out of the cave. Only the stair-like walls remain, which the silt has settled on.

The hot springs that push water out from inside the ground can clearly be seen in the cave, but the current does not affect diving. The water moves so slowly in the cave that you can hardly notice it when diving.

Buy the Book

Divers of the Dark

Publisher: Tammi ISBN: 978-951-31-4681-8 Size: 197 x 260 mm Pages: 160 Hard cover English translation by Marju Galitsos

The book is currently available through PayPal.

Get your PayPal copy here: